Showbiz & The Spanish Flu: Lessons from Last Century’s Pandemic

Dublin Core

Title

Showbiz & The Spanish Flu: Lessons from Last Century’s Pandemic

Subject

Spanish Flu

vaudeville

pandemics

COVID-19

influenza

Description

Similar to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the 1918 influenza pandemic shut down all entertainment across the U.S., from movie theaters to vaudeville houses.

Creator

Thom Wall

Source

Publisher

Circus Talk

Date

2020-03-31

Rights

Copyright 2020 Circus Talk

Format

application/pdf

Language

English

Type

Text

Identifier

THR-WP-05

Coverage

1918

United States

Text Item Type Metadata

Text

March 31, 2020

Thom Wall

COVID19CircusResponse_

The entertainment world is in a spiral, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cirque du Soleil has temporarily laid off 95% of its staff worldwide – some 4,679 people who worked for the 44 shows around the globe (Cole, 2020). Feld Entertainment, the parent company of the former Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus has also halted performances of Disney on Ice, Monster Jam, and other productions, also announcing its own rounds of layoffs (Jones, 2020). Cruise lines have halted their own operations, putting fly-on acts, production casts, technicians, and stage managers out of work (Patteson, 2020). Freelancers are also on the proverbial ropes, with thousands upon thousands of artists and other W-9 entertainment professionals finding themselves without work in the face of travel advisories, restrictions on public gatherings, and other rulings that run counter to our livelihoods in the interest of public health and safety (Facher, 2020).

This is unprecedented in our lifetimes, but has the entertainment industry ever taken such a massive hit in the face of public illness? To answer that question, we turn to the 1918 influenza pandemic.

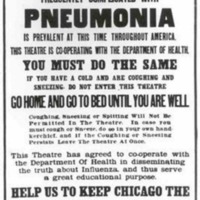

Image: Poster from a Chicago theater outlines flu regulations during the 1918 pandemic. Source: Smithsonian.Origins osu.edu

The 1918 influenza pandemic, known as the “Spanish flu” (much to the chagrin of Spaniards of the day), was the most severe pandemic in recent history. First identified in the spring of 1918, it quickly tore its way across the world and infected approximately 1/3 of the global population – killing 50 million people worldwide (CDC, 2020). This disease killed more people in a single year than the Black Plague of the 14th century – ending the lives of more Europeans and Americans than had died in the First World War by a factor of ten. This disease was incredibly infectious and could kill a person the day they were infected with the disease (Cullen, 2007).

As a response to this crisis, different cities attempted different responses, leading to a series of “quasi-experimental” responses to the flu across the United States with differing results (Foerster, 2017). However, one thing was as true then as it is today – the entertainment sector took a brutal hit.

In October of 1918,The Atlanta Constitution offered this grim description:

The influx of the Spanish “flue” [sic] has done more to disrupt the itineraries of the theatrical companies booked through this section of the country than anything that has ever happened before in the memory of the oldest inhabitant…

The sudden closing of the theaters has hit the theatrical people in this section of the country a very hard blow. When the order was given to close in this city on Monday, there was the big “Bringing-Up Father” company and over fifteen vaudeville acts in the city prepared to go on in the evening.(The Atlanta Constitution, 1918)

Although this was a severe hardship for everyone in the business, the same newspaper reported that theater owners and theatrical union leaders expressed “their entire willingness to take whatever action the board [of health] deemed best, repaired to their houses of entertainment and ordered the sale of tickets to be stoped [sic]” (The Atlanta Constitution, 1918). This action put an end to all show-business in the city of Atlanta as soon as word reached managers of theaters, vaudeville houses, and cinemas.

In Atlanta, vaudeville and variety performers descended on the Peachtree hotel as contracts were canceled left and right. “The big lobby was filled with actors, actresses and the near kind of both. It was a safe bet that a competent stage director could cast from the crowd in that lobby any one of the standard comedies or Shakespearian plays… a well-known vaudevillian was setting a crowd of his fellows in roars over his description of a hotel at Cordele… The present closing is working a real hardship on many of the players, but they are accepting it cheerfully and philosophically” (The Atlanta Constitution, 1918).

Chicago, Illinois had a similar response to Atlanta, Georgia and closed all movie theaters and vaudeville houses – and also passed ordinances against public spitting alongside the (now ubiquitous) educational messages about hand-washing and hand-shaking (Rosner, 2010). Philadelphia closed all places of gathering, including vaudeville houses and movie theaters. In Tuscon, Arizona people were not allowed to leave home without a face mask. A 1918 Albuquerque, New Mexico newspaper remarked as the announcement to close theaters was issued that “the ghost of fear walked everywhere” (Kolata, 2020).

Not all took the government’s advice so earnestly, however.

In Butte, Montana, when theaters were finally closed by the state, the Rialto theater projected the following poem on their screen as a poke in the ribs of a seemingly over-reacting government:

Our town is an awful stew,

And everybody’s feeling blue.

We hardly know just what to do

To overcome the Spanish Flu…

Two days later, the entire city of Butte, Montana was under quarantine. The next week, the Butte Miner’s front page read in bold letters “Spanish Flu is not a Joke” (Welsch, 2020).

In New York, the business community also pushed back against the government’s interventions – especially against their attempts to restrict ticket sales in theaters and movie houses. When Charlie Chaplin’s film Shoulder Arms was released in the fall of 1918, the manager of Times Square’s Strand Theatre praised his customers for their incredible turnout. He died of the flu a few weeks later (Spinney, 2020).

In Cincinnati, theater owners managed to convince the city to allow their halls to stay open for an extra few days, so as to finish their current production’s run. In Columbus, the chamber of commerce petitioned to carry on with a symphony concert at their largest hall, insisting that it would only be the wealthy elite in attendance – a class of people assumed unlikely to spread disease. Not long after, at least one theater in Ohio was converted into a makeshift morgue with nurses embalming bodies in the aisles and on the stage, stacking the cadavers “like cordwood” (Robertson, n.d.).

Many cities around the US relaxed restrictions on public gathering when the number of new cases began to decline. In these cities, the premature annulment of the bans often led to a resurgence of influenza cases. The city of Milwaukee wisely noticed this trend and kept restrictions in place until the end of December 1918.

This pandemic had a lasting impact on the careers of many performers in peculiar ways. For example, when Nell Shipman, the celebrated Canadian actress and producer, was being considered for the leading role in James Curwood’s Back to God’s Country, she learned that Curwood was particularly interested in her for her luscious head of hair. She was forced to hide the fact that she had lost all of her hair in a bout with the Spanish Flu, and hid her loss under what must have been a spectacular wig. She reported that admitting to Curwood that she had gone bald would be “a fate worse than death: a disclosure, an unveiling, the fading of a dream” (Foerster, 2017). (She ended up getting the role.)

The Marx brothers were affected financially, as well. The famous group of vaudevillians were only just beginning their career in 1918, and were under engagement to produce their very first play –The Street Cinderella – when the Spanish Flu hit:

“The Street Cinderella” might have prospered but for Spanish Flu. In a strange twist on the concept of prevention, ‘Vaudeville theaters were only allowed to be half full – members of the audience had to leave the seat on either side empty so that they would not breathe on one another. To further protect themselves, many wore surgical masks, so even when they laughed the sound was muffled.’(Arnold, 2018)

Catharine Arnold, author of Pandemic 1918, calls this failed show “…another victim of flu, succumbing in Michigan to bad reviews and empty houses” (Arnold, 2018) – a feeling that likely resonates with circus performers around the globe.

Image: Source: The Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Pa

In Australia, the epidemic all but ended Harry Clay’s expansive music hall empire. By 1919, the Spanish Flu epidemic had forced the closure of most entertainment activities across the continent, leaving him to rebuild his theatrical brand with limited resources (Djubal, 1999). He was successful in this endeavor, and enjoyed many new successes until his passing in 1925 (Richards).

The showbiz world didn’t bounce back immediately after the flu, as thoughts of the pandemic and quarantine lingered in audiences’ minds. When Mae West, the notable American actress, singer, comedienne, and playwright returned to the vaudeville stage just a few short years later, she remarked that “…there was the memory of the Spanish flu epidemic. Maybe it was just all that change in the air. Anyway, audiences seemed restless. There was a pervasive feeling of the wiggles. I could sense it. I could even feel it, a sense of it myself” (Chandler, 2012).

Was there a silver lining? For some people there was. Although show business ground to a halt during the pandemic, vaudeville performer Molly Picon offered the following report:

I was doing a vaudeville act [in Boston] and suddenly all the theaters were ordered closed. I needed money to get back home to Philadelphia, so I went to this Jewish theater which was allowed to stay open. It was at the Grand Opera House… it was an old and famous theater where the Drews and the Barrymores and everybody played…I went there because I knew all the actors, some of whom appeared with me in Philadelphia when I was a child. I just went to get some money to go home. What happened?

I’ll tell you what happened! I met my husband there, I mean, the man who was to become my husband, Jacob Kalish. Instead of giving me the money to go home, he gave me a contract. Not a marriage contract on the spot, oh no, but a contract with the company. So, you see, I had the Spanish Flu for a matchmaker! As the old Yiddish proverb says, ‘God takes away with one hand and blesses with the other”(Kelly, 1976).

Will there be a light at the end of our tunnel soon? History seems to think not. All we can do is stick together and help one another where we can. Whether we like it or not, this is a moment that will define our generation’s relationship to the arts – both as artists and employees.

References

Arellano, G. (2020, 3 16). This isn't the first time a virus caused social panic. The Spanish flu did too. Los Angeles Times.

Arnold, C. (2018). Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. New York City: St. Martin's Publishing Group.

Bernhard, B. (2020, 3 20). St. Louis saw the deadly 1918 Spanish flu epidemic coming. Shutting down the city saved countless lives. Retrieved from St. Louis Post-Dispatch: https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/st-louis-saw-the-deadly-spanish-flu-epidemic-coming-shutting/article_52e5e46d-1f30-5f31-a706-786785692bb5.html

Carlin, D. (2020, 2 29). Lessons From New York's 1918 Flu Outbreak. Retrieved from Forbes.

CDC. (2020, 3 20). 1918 Pandemic (H1N1). Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chandler, C. (2012). She Always Knew How: Mae West, a personal biography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cole, B. (2020, 3 20). Cirque du Soleil lays off 95 percent of its workforce after coronavirus forces closure of all its shows globally. Retrieved from Newsweek.

Cullen, F. (2007). Vaudeville Old & New: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America. New York: Psychology Press.

Djubal, C. (1999). From minstrel tenor to vaudeville showman: Harry Clay, 'a friend of the Australia performer'. Australasian Drama Studies.

Epstein, A. (2020, 3 16). Coronavirus is devastating the global box office - but it could be much worse. Retrieved from Quartz.

Facher, L. (2020, 3 16). Trump urges people to avoid discretionary travel and limit gatherings to fewer than 10 people. Retrieved from StatNews.

Foerster, A. (2017). Nell Shipman and the American Silent Cinema. In A. Foerster, Women in the Silent Cinema (pp. 305-425). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Johnson, M. (2020, 3 7). How did Milwaukee fight off Spanish flu? It closed churches and schools. But not saloons. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Jones, J. A. (2020, 3 20). Feld Entertainment cancels all of its shows, begins layoffs as COVID-19 pandemic worsens. Retrieved from Bradenton Herald.

Kelly, K. (1976, 12 4). Why Molly Picon thanks Spanish flu. Boston Globe, p. 12.

Kolata, G. (2020, 3 9). Coronavirus Is Very Different From the Spanish Flu of 1918. Here's How. The New York Times.

Kopp, J., & McGovern, B. (2018, 10 27). 100 years ago, 'Spanish flu' shut down Philadelphia - and wiped out thousands. Philly Voice.

Larson, R. C. (2007). Simple MOdels of Influenza Progression within a Heterogeneous Population. Operations Research, 399-412.

Larson, R. C. (2007). Simple Models of Influenza Progression within a Heterogeneous Population. Operations Research, 399-412.

Patteson, C. (2020, 3 5). Coronavirus travel: See list of cruise line restrictions and cancellation policies (UPDATED). Retrieved from Today.

Richards, L. (n.d.). Harry Clay and Clays Theatres. History of Australian Theatre. Retrieved from hat-archive.com

Robertson, K. (n.d.). The Spanish Influenza Comes to Ohio. Retrieved from Ohio History Connection.

Rosner, D. (2010). "Spanish Flu, or Whatever it is..." The paradox of public health in a time of crisis. Public Health Reports, 37-47.

Spinney, L. (2020, 3 11). Closed Borders and 'black weddings': what the 1918 flu teaches us about coronavirus. The Guardian.

The Atlanta Constitution. (1918, 10 11). Atlanta Becomes Convention City for Stage People. The Atlanta Constitution, p. 6.

The Atlanta Constitution. (1918, 10 8). Public Gathering Places Closed by City Council for Two Months. The Atlanta Constitution, p. 1.

Welsch, J. (2020, 3 20). 1918 Spanish flu put 'lid down' on sports and other activities in hard-hit Montana. Retrieved from Missoulian.

This research project was inspired by a late-night conversation with Benjamin Domask-Ruh. Special thanks to Benjamin for planting the idea in my head!

All photos provided courtesy of Thom Wall. Feature photo source: Seattle Museum of History & Industry

Thom Wall

COVID19CircusResponse_

The entertainment world is in a spiral, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cirque du Soleil has temporarily laid off 95% of its staff worldwide – some 4,679 people who worked for the 44 shows around the globe (Cole, 2020). Feld Entertainment, the parent company of the former Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus has also halted performances of Disney on Ice, Monster Jam, and other productions, also announcing its own rounds of layoffs (Jones, 2020). Cruise lines have halted their own operations, putting fly-on acts, production casts, technicians, and stage managers out of work (Patteson, 2020). Freelancers are also on the proverbial ropes, with thousands upon thousands of artists and other W-9 entertainment professionals finding themselves without work in the face of travel advisories, restrictions on public gatherings, and other rulings that run counter to our livelihoods in the interest of public health and safety (Facher, 2020).

This is unprecedented in our lifetimes, but has the entertainment industry ever taken such a massive hit in the face of public illness? To answer that question, we turn to the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Image: Poster from a Chicago theater outlines flu regulations during the 1918 pandemic. Source: Smithsonian.Origins osu.edu

The 1918 influenza pandemic, known as the “Spanish flu” (much to the chagrin of Spaniards of the day), was the most severe pandemic in recent history. First identified in the spring of 1918, it quickly tore its way across the world and infected approximately 1/3 of the global population – killing 50 million people worldwide (CDC, 2020). This disease killed more people in a single year than the Black Plague of the 14th century – ending the lives of more Europeans and Americans than had died in the First World War by a factor of ten. This disease was incredibly infectious and could kill a person the day they were infected with the disease (Cullen, 2007).

As a response to this crisis, different cities attempted different responses, leading to a series of “quasi-experimental” responses to the flu across the United States with differing results (Foerster, 2017). However, one thing was as true then as it is today – the entertainment sector took a brutal hit.

In October of 1918,The Atlanta Constitution offered this grim description:

The influx of the Spanish “flue” [sic] has done more to disrupt the itineraries of the theatrical companies booked through this section of the country than anything that has ever happened before in the memory of the oldest inhabitant…

The sudden closing of the theaters has hit the theatrical people in this section of the country a very hard blow. When the order was given to close in this city on Monday, there was the big “Bringing-Up Father” company and over fifteen vaudeville acts in the city prepared to go on in the evening.(The Atlanta Constitution, 1918)

Although this was a severe hardship for everyone in the business, the same newspaper reported that theater owners and theatrical union leaders expressed “their entire willingness to take whatever action the board [of health] deemed best, repaired to their houses of entertainment and ordered the sale of tickets to be stoped [sic]” (The Atlanta Constitution, 1918). This action put an end to all show-business in the city of Atlanta as soon as word reached managers of theaters, vaudeville houses, and cinemas.

In Atlanta, vaudeville and variety performers descended on the Peachtree hotel as contracts were canceled left and right. “The big lobby was filled with actors, actresses and the near kind of both. It was a safe bet that a competent stage director could cast from the crowd in that lobby any one of the standard comedies or Shakespearian plays… a well-known vaudevillian was setting a crowd of his fellows in roars over his description of a hotel at Cordele… The present closing is working a real hardship on many of the players, but they are accepting it cheerfully and philosophically” (The Atlanta Constitution, 1918).

Chicago, Illinois had a similar response to Atlanta, Georgia and closed all movie theaters and vaudeville houses – and also passed ordinances against public spitting alongside the (now ubiquitous) educational messages about hand-washing and hand-shaking (Rosner, 2010). Philadelphia closed all places of gathering, including vaudeville houses and movie theaters. In Tuscon, Arizona people were not allowed to leave home without a face mask. A 1918 Albuquerque, New Mexico newspaper remarked as the announcement to close theaters was issued that “the ghost of fear walked everywhere” (Kolata, 2020).

Not all took the government’s advice so earnestly, however.

In Butte, Montana, when theaters were finally closed by the state, the Rialto theater projected the following poem on their screen as a poke in the ribs of a seemingly over-reacting government:

Our town is an awful stew,

And everybody’s feeling blue.

We hardly know just what to do

To overcome the Spanish Flu…

Two days later, the entire city of Butte, Montana was under quarantine. The next week, the Butte Miner’s front page read in bold letters “Spanish Flu is not a Joke” (Welsch, 2020).

In New York, the business community also pushed back against the government’s interventions – especially against their attempts to restrict ticket sales in theaters and movie houses. When Charlie Chaplin’s film Shoulder Arms was released in the fall of 1918, the manager of Times Square’s Strand Theatre praised his customers for their incredible turnout. He died of the flu a few weeks later (Spinney, 2020).

In Cincinnati, theater owners managed to convince the city to allow their halls to stay open for an extra few days, so as to finish their current production’s run. In Columbus, the chamber of commerce petitioned to carry on with a symphony concert at their largest hall, insisting that it would only be the wealthy elite in attendance – a class of people assumed unlikely to spread disease. Not long after, at least one theater in Ohio was converted into a makeshift morgue with nurses embalming bodies in the aisles and on the stage, stacking the cadavers “like cordwood” (Robertson, n.d.).

Many cities around the US relaxed restrictions on public gathering when the number of new cases began to decline. In these cities, the premature annulment of the bans often led to a resurgence of influenza cases. The city of Milwaukee wisely noticed this trend and kept restrictions in place until the end of December 1918.

This pandemic had a lasting impact on the careers of many performers in peculiar ways. For example, when Nell Shipman, the celebrated Canadian actress and producer, was being considered for the leading role in James Curwood’s Back to God’s Country, she learned that Curwood was particularly interested in her for her luscious head of hair. She was forced to hide the fact that she had lost all of her hair in a bout with the Spanish Flu, and hid her loss under what must have been a spectacular wig. She reported that admitting to Curwood that she had gone bald would be “a fate worse than death: a disclosure, an unveiling, the fading of a dream” (Foerster, 2017). (She ended up getting the role.)

The Marx brothers were affected financially, as well. The famous group of vaudevillians were only just beginning their career in 1918, and were under engagement to produce their very first play –The Street Cinderella – when the Spanish Flu hit:

“The Street Cinderella” might have prospered but for Spanish Flu. In a strange twist on the concept of prevention, ‘Vaudeville theaters were only allowed to be half full – members of the audience had to leave the seat on either side empty so that they would not breathe on one another. To further protect themselves, many wore surgical masks, so even when they laughed the sound was muffled.’(Arnold, 2018)

Catharine Arnold, author of Pandemic 1918, calls this failed show “…another victim of flu, succumbing in Michigan to bad reviews and empty houses” (Arnold, 2018) – a feeling that likely resonates with circus performers around the globe.

Image: Source: The Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Pa

In Australia, the epidemic all but ended Harry Clay’s expansive music hall empire. By 1919, the Spanish Flu epidemic had forced the closure of most entertainment activities across the continent, leaving him to rebuild his theatrical brand with limited resources (Djubal, 1999). He was successful in this endeavor, and enjoyed many new successes until his passing in 1925 (Richards).

The showbiz world didn’t bounce back immediately after the flu, as thoughts of the pandemic and quarantine lingered in audiences’ minds. When Mae West, the notable American actress, singer, comedienne, and playwright returned to the vaudeville stage just a few short years later, she remarked that “…there was the memory of the Spanish flu epidemic. Maybe it was just all that change in the air. Anyway, audiences seemed restless. There was a pervasive feeling of the wiggles. I could sense it. I could even feel it, a sense of it myself” (Chandler, 2012).

Was there a silver lining? For some people there was. Although show business ground to a halt during the pandemic, vaudeville performer Molly Picon offered the following report:

I was doing a vaudeville act [in Boston] and suddenly all the theaters were ordered closed. I needed money to get back home to Philadelphia, so I went to this Jewish theater which was allowed to stay open. It was at the Grand Opera House… it was an old and famous theater where the Drews and the Barrymores and everybody played…I went there because I knew all the actors, some of whom appeared with me in Philadelphia when I was a child. I just went to get some money to go home. What happened?

I’ll tell you what happened! I met my husband there, I mean, the man who was to become my husband, Jacob Kalish. Instead of giving me the money to go home, he gave me a contract. Not a marriage contract on the spot, oh no, but a contract with the company. So, you see, I had the Spanish Flu for a matchmaker! As the old Yiddish proverb says, ‘God takes away with one hand and blesses with the other”(Kelly, 1976).

Will there be a light at the end of our tunnel soon? History seems to think not. All we can do is stick together and help one another where we can. Whether we like it or not, this is a moment that will define our generation’s relationship to the arts – both as artists and employees.

References

Arellano, G. (2020, 3 16). This isn't the first time a virus caused social panic. The Spanish flu did too. Los Angeles Times.

Arnold, C. (2018). Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. New York City: St. Martin's Publishing Group.

Bernhard, B. (2020, 3 20). St. Louis saw the deadly 1918 Spanish flu epidemic coming. Shutting down the city saved countless lives. Retrieved from St. Louis Post-Dispatch: https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/st-louis-saw-the-deadly-spanish-flu-epidemic-coming-shutting/article_52e5e46d-1f30-5f31-a706-786785692bb5.html

Carlin, D. (2020, 2 29). Lessons From New York's 1918 Flu Outbreak. Retrieved from Forbes.

CDC. (2020, 3 20). 1918 Pandemic (H1N1). Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chandler, C. (2012). She Always Knew How: Mae West, a personal biography. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cole, B. (2020, 3 20). Cirque du Soleil lays off 95 percent of its workforce after coronavirus forces closure of all its shows globally. Retrieved from Newsweek.

Cullen, F. (2007). Vaudeville Old & New: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America. New York: Psychology Press.

Djubal, C. (1999). From minstrel tenor to vaudeville showman: Harry Clay, 'a friend of the Australia performer'. Australasian Drama Studies.

Epstein, A. (2020, 3 16). Coronavirus is devastating the global box office - but it could be much worse. Retrieved from Quartz.

Facher, L. (2020, 3 16). Trump urges people to avoid discretionary travel and limit gatherings to fewer than 10 people. Retrieved from StatNews.

Foerster, A. (2017). Nell Shipman and the American Silent Cinema. In A. Foerster, Women in the Silent Cinema (pp. 305-425). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Johnson, M. (2020, 3 7). How did Milwaukee fight off Spanish flu? It closed churches and schools. But not saloons. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Jones, J. A. (2020, 3 20). Feld Entertainment cancels all of its shows, begins layoffs as COVID-19 pandemic worsens. Retrieved from Bradenton Herald.

Kelly, K. (1976, 12 4). Why Molly Picon thanks Spanish flu. Boston Globe, p. 12.

Kolata, G. (2020, 3 9). Coronavirus Is Very Different From the Spanish Flu of 1918. Here's How. The New York Times.

Kopp, J., & McGovern, B. (2018, 10 27). 100 years ago, 'Spanish flu' shut down Philadelphia - and wiped out thousands. Philly Voice.

Larson, R. C. (2007). Simple MOdels of Influenza Progression within a Heterogeneous Population. Operations Research, 399-412.

Larson, R. C. (2007). Simple Models of Influenza Progression within a Heterogeneous Population. Operations Research, 399-412.

Patteson, C. (2020, 3 5). Coronavirus travel: See list of cruise line restrictions and cancellation policies (UPDATED). Retrieved from Today.

Richards, L. (n.d.). Harry Clay and Clays Theatres. History of Australian Theatre. Retrieved from hat-archive.com

Robertson, K. (n.d.). The Spanish Influenza Comes to Ohio. Retrieved from Ohio History Connection.

Rosner, D. (2010). "Spanish Flu, or Whatever it is..." The paradox of public health in a time of crisis. Public Health Reports, 37-47.

Spinney, L. (2020, 3 11). Closed Borders and 'black weddings': what the 1918 flu teaches us about coronavirus. The Guardian.

The Atlanta Constitution. (1918, 10 11). Atlanta Becomes Convention City for Stage People. The Atlanta Constitution, p. 6.

The Atlanta Constitution. (1918, 10 8). Public Gathering Places Closed by City Council for Two Months. The Atlanta Constitution, p. 1.

Welsch, J. (2020, 3 20). 1918 Spanish flu put 'lid down' on sports and other activities in hard-hit Montana. Retrieved from Missoulian.

This research project was inspired by a late-night conversation with Benjamin Domask-Ruh. Special thanks to Benjamin for planting the idea in my head!

All photos provided courtesy of Thom Wall. Feature photo source: Seattle Museum of History & Industry

Original Format

website

Collection

Citation

Thom Wall, “Showbiz & The Spanish Flu: Lessons from Last Century’s Pandemic,” Dominican University SOIS Omeka Site, accessed November 17, 2024, http://108.166.64.190/omeka222/items/show/2326.